The magazine “Die Kehre” wants to restore nature conservation on the right-wing fringe. And at the same time greening the ethnic wing of the AfD.

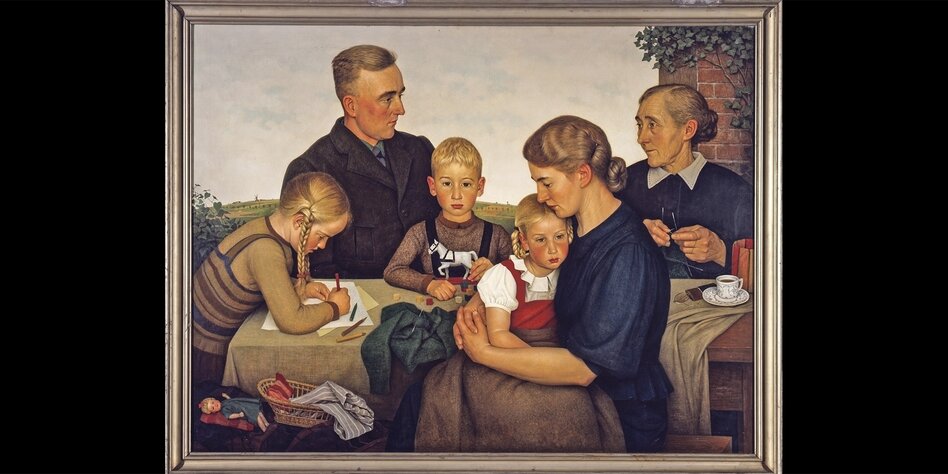

Like an idyll echoes of the new right: “The Farming Family Kalenberg” by Adolf Wissel, 1939 Photo: Arne Psille/DHM/bpk

Green, left-wing and ecological: this is a triad that somehow fits perfectly in Germany. But this worries a group of right-wingers. Magazine The curve by editor-in-chief Jonas Schick, from the Identitarian Movement, wants to refocus the issue of “ecology” on the extreme right.

In the first issue, published in 2020, Schick calls for “stopping the current reduction of ecology to 'climate protection' and broadening the vision of what its original meaning is: that it is a doctrine of the entire environment, “which includes cultural landscapes, rituals and customs, including the house and farm (Oikos) as its namesake.”

will be distributed Sweep from Oikos Verlag, headed by Philip Stein since June 2023. Stein also heads the new right-wing association One Percent. The association is considered the front organization of the AfD's ethnic camp. And editor-in-chief Schick also hired AfD Bundestag member René Springer last year.

It is therefore not surprising that Björn Höcke is allowed to explain in a long interview how important “the preservation and maintenance of our traditional cultural landscape” is to him. “We have to take the issue of nature conservation away from the Greens,” says Höcke, “because it is what is good for us.”

Rights for nature conservation

In fact, rights have shaped the environmental and conservation movement since the 19th century. Thinkers such as Ernst Moritz Arndt countered the emerging industrial modernity with the German forest, which they considered necessary to protect on the one hand and provide identity to the nation on the other. The Nazis took up this myth. Once they came to power, they designated new nature reserves and promoted waste recycling. However, after 1945, environmental protection took a backseat as German reconstruction grew.

In the 1970s, West German leftists increasingly campaigned for ecological concerns. They met in the Green Party and soon expelled the conservatives and old Nazis who were initially there as well.

They want to counteract this shift to the left of German ecology Sweep write now. The magazine has a matte design, is published quarterly and costs 10 euros. In addition to essays on nature and sustainability (in old spelling, of course), you can also find short reports on studies on glyphosate or the bird of the year 2023 (the northern stonechat). Like many people, it is usually between 60 and 80 pages. Sweep Schick does not want to reveal who reads it and who finances it; the corresponding taz question remains unanswered.

Against “green growth”

But what ideas does she represent? Predominantly busy Sweep with themes similar to progressive echoes, but with different accents. Take climate change, for example: it is hardly directly denied in this magazine. The almost exclusively male authors repeatedly flirt with the idea that human CO2Emissions may not be the main cause of global warming. They still want to move away from the massive use of fossil fuels for reasons of nature conservation.

that's horrible Sweep “green growth” for the good of the climate. Nature conservation is affected by climate protection, writes Schick: “Wind turbines destroy birds, bats and insects, biomass cultivation promotes land degradation through overly fertilized monocultures and the extraction of cobalt for production of 'green technology' in the Congo leaves latent wounds, both ecological and social.”

The magazine's title comes from an essay by philosopher Martin Heidegger. In “Technology and the Curve,” Heidegger presents modern technology as a danger because it blocks people’s access to their authentic “being.” But this danger also gives rise to the possibility of a “turn,” says Heidegger, a return to the original, to nature and home.

This is linked to this alternative to industrial modernity. Sweep in. Like Heidegger's ideological model, she is concerned with the conservation of the forests and grasslands, which he considers the ancestral homeland of the Germans.

What is surprising is that the New Right presents its critique of modernity with more fervor than the alternative eco-s. That's not surprising. It is probably, at least implicitly clear, to many left alternatives that industrial society has historically made possible the social liberalizations they want to preserve and expand. The far right, on the other hand, also wants to reverse this progress.

The bioregion for the Germans

GDR environmental lawyer Michael Beleites, who previously worked at Greenpeace but now lectures at the new right-wing State Policy Institute, therefore calls for saying goodbye to economic growth and returning to the countryside. The slogan in Sweep because this is “bioregionalism”.

But quickly it is about not only flora and fauna, but about “maintaining the 'relative unity of people and space', which must not be allowed to perish through uncontrolled immigration in a multi-ethnic and multicultural arbitrariness” due to the De Otherwise, “the human base would disappear,” writes author Hagen Eichberger.

Alain de Benoist, the French pioneer of the new right, is outraged sweep, “That many environmentalists who care about preserving biodiversity are indifferent to the loss of the diversity of peoples and cultures.” In this sense, a caption describes the immigrant-dominated Karl-Marx-Strasse in Berlin-Neukölln as the “epicenter of uprooting.”

Fear of “overpopulation”

When the authors talk about immigration, concern about the supposed “overpopulation” of the planet is not far away. Conservationist Lotta Bergemann warns in the Sweep faces an “ecocollapse” if the world population does not “stabilize at a low level.”

Höcke thinks the same way, and refers to the animal researcher and National Socialist Konrad Lorenz, who noted “that ecological laws also apply to humans. There can be no eternal growth, not even in demographic development. If we cannot stop it through a fundamental change in consciousness, then nature will intervene in a regulatory way, but certainly in a way that will not seem very human to us.

The ideas are reminiscent of those of the American author Paul R. Ehrlich, who wrote in 1968 in “The Population Bomb” about the supposedly natural limits of human growth, but his predictions of mass extinction turned out to be scandalous. Apparently, the new right still longs for that mass death, even if they know how to express their desire in euphemistic language. But Schick complains about the accusation: the left “would see Auschwitz looming again on the horizon behind the demand for a reduction in the world population.”

Political ambitions

Regardless of the lofty claims, the political impact remains Sweep weak. Schick admitted in 2020 that he had not yet managed to get an “ecologically and socially conservative” position in the AfD to a majority. In an interview with Schick, Höcke added that we still have to “develop concepts for the day when it becomes clear that the established policy with its unilateral dogma of growth has come to an end. The theoretical work must be done now.”

Furthermore, the right would have to “qualitatively expand the concept of standard of living to put the material aspect into perspective.” So far, AfD voters seem to be more concerned about their material interests than small farmers and natural folklore.

Ecology instead of fascism

The Nazis also had to confront this contradiction between material concerns and nature conservation. Despite blood and dirt folklore, they cut paths through forests and fields to build the highway and produced tanks and rockets on an assembly line. In one Sweep-The text praises Andreas Karsten, editor-in-chief of the right-wing magazine First! – the “National Socialist conception of forests” and the designation of new nature reserves by the NSDAP.

The echoes of the new right would prefer to return to the supposedly simpler and more harmonious living conditions of yesteryear: the home, the farm, the community and the patriarchal family.

Schick, on the other hand, distances himself from fascism on the same issue because it is too modern for him. Fascist approaches “that want to direct 'progress' in a nationalist sense” are diametrically opposed to right-wing environmental politics, he writes. “Fascism was a revolutionary and radical right-wing movement. […] Schick does not want to adopt the idea of “ecofascism,” which Jewish philosopher André Gorz critically analyzes: “ecology” and “fascism” cannot be used. bind.

Instead, echoes of the new right want to break with modernity as much as possible. They pursue two long-term objectives: to shift the entire ecological discourse to the right and to green the AfD. They would prefer to return to the supposedly simpler and more harmonious living conditions of yesteryear: the home, the farm, the community and the patriarchal family. All this fits perfectly into the holistic and ecological thinking of the Sweep.