Women and people of migrant background are especially affected by online violence. The editors of the study warn that the diversity of opinions is being affected.

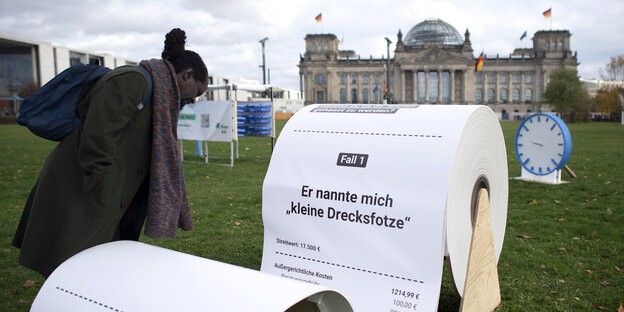

Stop Hate Aid protest in front of the Reichstag in Berlin in November 2023 Photo: Stefan Bones

SEDAN taz | The online climate is becoming increasingly hostile. Hate messages and sexual violence are increasing, but diverse speech is decreasing. The representative study “Strong hatred – silent withdrawal. How hate on the Internet threatens democratic discourse,” warns the “Competition Network against Hate” about the consequences of digital violence. To find out how Internet users deal with hate messages and who is especially affected, the network digitally surveyed more than 3,000 people aged 16 and over about their behavior on the Internet. The study was carried out by Das NETTZ, the Society for Media Education and Communication Culture (GMK), HateAid and New German Media Makers.

“Hate on the Internet is omnipresent,” said Federal Family Minister Lisa Paus (Greens) when presenting the results of the study on Tuesday morning. A first national survey in 2019 by the Institute for Democracy and Civil Society (IDZ) warned of the growing scope of discrimination and threats of violence online.

The current study continues the negative trend and shows how hate appears to be becoming normalized online. “Online hate is an attack on diversity of opinion. It can affect everyone, but not everyone equally,” says Elena Kountidou, CEO of New German Media Makers. The focus is especially on young people, as well as people with visible migration backgrounds and queer people.

A third of each of the last two groups mentioned say they are affected. Among young people between 16 and 24 years old, who especially use platforms such as Tiktok and Instagram, women are especially victims of digital violence. Nearly one in three reports hate online.

A quarter say they deactivate their profiles

The definition of hate on the Internet goes beyond hate speech; It also includes sexual violence, harassment or doxing and the publication of personal data. Most of the time, hate is related to the political opinions of those affected and their appearance. Digital violence often takes the form of insults and false accusations.

What is considered hate is individual. When asked the specific question, “Have you been affected by online hate?”, 15 percent of respondents agreed. However, about a quarter of respondents said they frequently experienced at least one form of hate online. The study explains the differences by saying that not all online insults are considered hate. Younger people, in particular, seem to accept this as normal to some extent.

Rüdiger Fries, from the Society for Media Education and Communication Culture, warns of the consequences for those affected and digital discourse. 82 percent of those affected blocked or reported their authors. A quarter of those affected claim to deactivate or delete their profiles. The field will be left in the hands of the haters as hostile people withdraw from the discourse.

To strengthen discourse and democracy in the digital world, the skills network requires comprehensive advice on media skills in schools and companies. Platform providers should also be more responsible.