Journalistic work in China is increasingly difficult, foreign correspondents there complain. One in two people report harassment by the police.

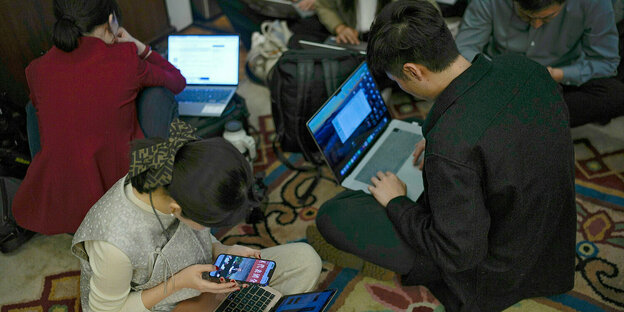

Journalists on the sidelines of the National People's Congress. Working in China is increasingly difficult for foreign colleagues Photo: Andy Wong/ap

SEDAN taz | In the southwestern Chinese metropolis of Chengdu, a handful of citizens are protesting in front of a bank against the Sichuan Trust, which local media reports is in trouble. Protesters feel defrauded of their deposits and shout, “Give us our money back” during their protest in late February. When the China correspondent for Dutch public broadcaster NOS, Sjoerd den Daas, wants to talk to them, he is turned away by a man and a police officer.

The man, apparently a plainclothes police officer, pushes the journalist to the ground, who is protesting against the treatment he has received. He unsuccessfully pointed to her press card and his accreditation, but they took her bag and microphone. He is then taken to a police van and taken away with his camerawoman.

At the station, their mobile phones and cameras are confiscated and they are also denied a phone call, as the Foreign Correspondents' Club in China (FCCC) later reported. Only after hours were Chinese Foreign Ministry officials able to secure the release of the NOS team. But later, the two are followed by numerous vehicles, preventing any contact with the population and any independent information. Under Chinese law, accredited foreign correspondents have the right to speak to people in China, as long as they do not object.

The actions of local authorities against Sjoerd den Daas are part of the daily life of foreign correspondents in China, as shown in the FCCC report on its annual survey published this Monday. The only special thing about the case is that it was filmed. But in the FCC report, 54 percent of respondents complained of obstructions by police or other officials and 37 percent of those interviewed refused to answer due to pressure from officials.

“We had a very pleasant interview in a village with a former kindergarten teacher who now works as a caregiver for the elderly, reports a European correspondent who wishes to remain anonymous. “But after the conversation, five plainclothes police officers stopped us and confronted a representative of the authorities. A few hours later we received a call from our protagonist. “She threatened to sue us if we published the interview.”

Post-Covid resorts to old methods of intimidation

In the report, which is based on a survey of its 157 members from 30 countries, the FCCC first welcomes the fact that with the abolition of extensive Covid restrictions in China, they can no longer be used to suppress the Informs presentation.

Authorities have since resorted to other methods. Today, only 13 percent of respondents said they could do research like they did before the pandemic. However, 99 percent say conditions in China barely or do not meet international reporting standards.

The report is notably characterized by an effort to differentiate itself. In it, the FCCC notes some minimal improvements in correspondents' work, but describes a general trend toward further deterioration. In particular, surveillance of foreign journalists, now sometimes even with drones, has increased, as has intimidation.

Fewer visas, fewer journalists

Previous practices such as “invitations to tea” by State security continue, that is, possible warnings and intimidation of journalists. And with one exception, American media outlets were not allowed to swap employees or accredit new ones to China. 32 percent of female correspondents complained of staff shortages due to denial of visas to journalists.

Only one journalist received accreditation for the Indian media. The FCCC also complains about restrictions on short-term and visiting visas for journalists.

Research in Tibet, Xinjiang or Inner Mongolia has always been difficult or even impossible. “At one point, six vehicles were following us,” a European journalist told the FCCC about his trip to Xinjiang. Another reported from China's Western Province: “We could no longer continue working in the village for fear of our interview partners.”

More “sensitive areas”

According to the report, what is now also new is greater monitoring of journalistic investigation in border areas with neighboring countries. 79 percent of respondents reported problems, especially near the Russian border. Another new quality is the warnings to correspondents not to join the FCCC or its board of directors. Because it is an “illegal organization.”

China currently occupies 179th place out of 180 in the press freedom ranking of the Reporters Without Borders organization, only North Korea is in an even worse position.