Italy also has an ambivalent attitude towards its left-wing terrorist group. Some former members of the “Red Brigade” continue to be persecuted today.

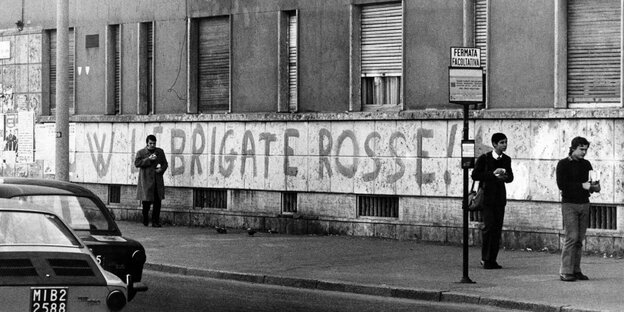

A graphite for the “Brigate Rosse” of Milan in 1977 Photo: Adriano Alecchi/Mondadori Portfolio/getty magesGraffit of the Red Brigadebn

The parallels are striking. Like the RAF in Germany, the Brigate Rosse (BR) in Italy began its armed struggle in the early 1970s. With murders of police officers, politicians, managers, journalists. With the kidnapping of Hanns Martin Schleyer or the prominent Christian Democrat politician Aldo Moro. With bank and gun store robberies.

And, just as in Germany, that meant for terrorists: They had to go underground, until they were killed in a shootout with police or until they were arrested and spent years in prison.

In both countries, the combatants of that time are already of retirement age. Their organizations laid down their arms decades ago. We can no longer speak of a serious left-wing terrorist threat.

But there is a striking difference between the two countries. In Germany only a few dozen people took up arms for the RAF, while in Italy there were hundreds of fighters who went into hiding, as well as a support and sympathizer scene of several thousand people.

More than a thousand accused

Around 1,200 defendants were brought before the courts as members of the Red Brigades or organizations derived from them, and at least the same number were active in “smaller” terrorist formations; Only the second largest organization after the BR, Prima Linea, had around 900 active members against whom the judiciary was investigating. In total, the number of leftist terrorists arrested in the 1970s and 1980s is estimated at 4,000.

The Brigate Rosse and the other groups left a long trail of blood in the country: 197 people were victims of them, the last to die was labor law professor Marco Biagi, shot dead by the “New BR” in 2002. The The State, for its part, reacted with great severity and locked up the captured terrorists in high-security prisons.

Following the kidnapping of US General James Lee Dozier in December 1981 and his subsequent release by police, it became clear that investigators had only been able to locate the kidnapping squad through the torture of prisoners.

And to this day the accusation remains that when agents raided a BR hideout in Genoa in March 1980, they deliberately executed at least one of the four brigade members who were allegedly shot in a “shootout” after had been disarmed.

Italy approached the terrorists

In addition to extreme harshness, the Italian State, in a peculiar dialectic, also relied on a high degree of flexibility when dealing with the activists of terrorist groups who had fallen into its network. First of all, there was the indulgence program, which was introduced by law in 1982. “Pentiti”, “penitents”, is what those who unpack are called in Italy. Those who fought for the BR not only confessed to their own crimes, but also named their accomplices, could expect a significant reduction in their sentence. The “life sentence” was converted to 10 years in prison and all other time-limited sentences were halved.

That law was the beginning of the end of left-wing terrorism in Italy. Patrizio Peci, a prominent red brigadier who was arrested by the police in 1980, immediately unpacked and then became an important witness in court, handed hundreds of fighters to the knife and was sentenced to only eight years in prison.

Although the Red Brigades took cruel revenge on him, kidnapping and murdering his brother, Peci was not left alone. In the following years, dozens of members of Brigate Rosse, Prima Linea and other groups testified, leading to the arrest of hundreds of militants and, in turn, receiving lesser prison sentences, even when they were involved in numerous murders.

But the state also made an offer to those who did not want to testify against their fellow activists. There were two laws on this matter in 1980 and 1987. dissociation, the “renunciation” of the armed struggle against the State. As soon as they declared that they had broken with their terrorist past, they too could expect a reduced sentence. Valerio Morucci, for example, was one of the leaders of the Red Brigades in Rome and was part of the commando that kidnapped the politician Aldo Moro on March 16, 1978 and murdered his five bodyguards, while Moro himself was shot by the BR in May. 9 should.

Along with his then partner Adriana Faranda, Morucci separated from the BR struggle shortly after his arrest in 1979; At the trial for Moro's kidnapping, she read a document signed by 170 prisoners titled: “Reopen dialogue with society.” The courts honored this with a significant reduction in his sentence, and he, who was actually expected to be sentenced to life in prison, was released in 1990.

Hiding in France

The Italian State even extended its hand to those who did not want to show up or give up the armed struggle. There is Renato Curcio, another founder of the Red Brigades, or Barbara Balzerani, leader of the BR. Both always recognized the history of their organization, but at the same time declared in 1987 that the armed struggle was now a thing of history in view of changing historical conditions.

This was enough for the courts to grant Curcio, who had been arrested in 1976, parole in 1992 and finally release him in 1998. Barbara Balzerani, convicted of several murders and arrested in 1985, was also paroled. in 2006.

Does this make Italy a counter-model to Germany, which is celebrating having finally arrested RAF pensioner Daniela Klette? Unlikely. Because there are not only three BR prisoners who speak out in favor of armed struggle who are still in high security detention. The Italian State also does not want to abandon the search for ex-combatants who have long since reached retirement age.

An example of this is Cesare Battisti, sentenced in absentia to life imprisonment for several murders. He had been on the run for decades and had built a new life as a celebrated writer, especially in France, but in 2019 Italian investigators captured the then 64-year-old in Bolivia and secured his extradition. He has been in custody since then.

Italy also wants to see the ten grizzled terrorists who had found refuge in France since the 1980s behind bars; The youngest is now 63 years old, the oldest has already celebrated his 80th birthday. France was to BR deserters what the GDR was to weary RAF fighters: a safe haven in which they were protected from extradition. They thanked the so-called Mitterrand Doctrine for this: in 1985, the then French president, François Mitterrand, promised protection in France to all members of terrorist groups who were not guilty of murder.

Italian governments of all stripes repeatedly attacked the protection granted by France, filing one extradition request after another. And in April 2021, persistence appeared to be successful: seven former terrorists were detained in Paris for extradition and arrest warrants were issued for three other people who had gone into hiding. French President Emmanuel Macron had declared his consent to the extradition with the words: “Those people who have committed atrocities deserve to be tried in Italy.”

But France's highest court stood in the way. Firstly, the wanted persons were convicted in absentia in Italy, with no hope of a new trial after extradition. And secondly, they have lived between 25 and 40 years in France, “a country in which they have a stable family situation, so their extradition would constitute an undue prejudice to their right to respect for their private and family life.”

Italy reacted immediately with a resolution approved by all parties except the radical left “Green-Left Alliance” in the House of Representatives, according to which the European Court of Human Rights should revoke Paris' no to extradition. The Italian state, like the German state, has apparently adopted an old terrorist slogan: “The fight continues.”